The eve of the PEN International Annual Congress, this time in Oxford, was chilly and sodden. I arrived at night. Flood alerts lighted up my phone. The theme of the conference, “Writers in a World at War,” and the dark and desolate plaza where the coach from Heathrow left me off, set the serious tone with hammering rain, little shelter and a troubling absence of taxis.

PEN is a global writing community whose long-standing mission is to protect freedom of expression, to celebrate the literary arts, and to foster solidarity among writers. It was born in 1921 in London, out of the turmoil of World War I. The acronym P.E.N. stands for “Poets, Essayists, Novelists,” but the membership has broadened over the last century to include journalists, broadcasters, artists, and other cultural professionals. Over 130 PEN centers dot the globe. The yearly congress usually takes place in different parts of the world. However, during the pandemic and again last year, the annual congress was held mostly online.

Despite the torrents of rain greeting my arrival in Oxford, or perhaps all the more because of it, the mood among the PEN delegates from over 90 countries gathered at the Leonardo Royal Hotel was warm, inquisitive, and happy at seeing old friends. Yet serious business was afoot.

PEN International has four working committees: Writers in Prison; Women Writers; Writers for Peace; Translation and Linguistic Rights. The first day of the conference was devoted to meetings of those committees. I was representing San Miguel PEN, an English-speaking center based in San Miguel de Allende, in central Mexico. We were excited that a president emerita of our PEN center, Judyth Hill, was standing for election as head of PEN International Women Writers Committee. Judyth and Lucina Kathmann, the third member of San Miguel PEN’s delegation, spent that first day of the conference at the Women Writers Committee meeting. I elected to attend the meeting for the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC). After all, Mexico is home to 68 indigenous groups, each with its own language and its variants. The motto of the TLRC is “Making Silenced Languages Visible.”

In June of this year, the TLRC had met in person in Sápmi (Finland) in celebration of the Sámi indigenous language, a language spoken in parts of northern Finland, Sweden, Norway, and one small area of Russia. During this 90th Congress, PEN adopted a declaration urging the promotion of Sámi literature and education within the countries where the Sámi peoples live.

Another successful project of the TLRC this year was the continuation of the month-long video marathon of poems in indigenous and minoritized languages, a project initiated in 2021, and shepherded by committee chair Urtzi Urrutikoetxea of Basque PEN. For the first time this year, San Miguel PEN was fortunate to be able to submit two videos to the marathon in honor of International Mother Language Day, February 21 (the day was established by the UN General Assembly in 2007, as part of efforts to “promote the preservation and protection of all languages used by people of the world”). The video entries of San Miguel PEN featured a poet from the Oaxaca area reading in the Zapotec language, and another poet from the Chiapas area reading in Zoque. Viewership of this marathon continues to grow each year; 30 new languages were added in 2024, Zapotec (our San Miguel submission) among them. I was impressed by the diversity of the attendees at this TLRC meeting, with representation from, among many other countries, Togo, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bolivia, Malawi, and Denmark.

Many moments stood out for me in the succeeding days of the Congress and linger still. One is the “Empty Chair” on the dais at the start of each day’s session to mark the absence of a writer because of imprisonment. One day we remembered Pham Doan Trang, a Vietnamese journalist and activist in prison since 2021, for “conducting propaganda against the State of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.” Another was Alaa Abd El-Fattah, blogger and government critic tortured and jailed in Egypt during the last five years for “spreading false news.”

The formal opening of PEN’s general assembly began with a moving reflection by Palestinian author Adania Shibli. Other lingering moments include the stories of writers, some attending the congress, such as the poet and novelist Gioconda Belli, in exile from Nicaragua, who had lost their employment, homes and even citizenship because something they wrote offended, implicated, or exposed someone in power.

The formal opening of PEN’s general assembly began with a moving reflection by Palestinian author Adania Shibli. Other lingering moments include the stories of writers, some attending the congress, such as the poet and novelist Gioconda Belli, in exile from Nicaragua, who had lost their employment, homes and even citizenship because something they wrote offended, implicated, or exposed someone in power.

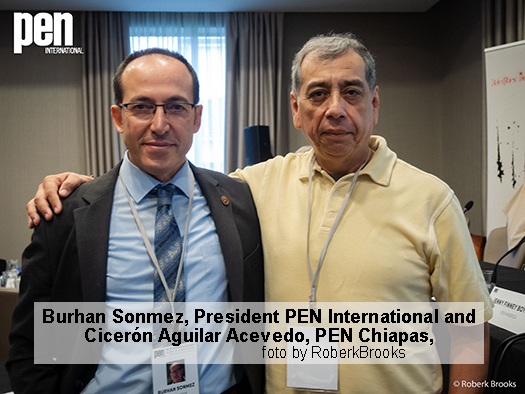

Also sobering was the prohibition against our taking personal photos at the Congress and posting them on social media because of the harm that could come to certain delegates should their governments know they were attending the conference. The realities under which many writers around the globe labor are often shockingly unjust and draconian.

In keeping with our mission to be vigilant about violations of freedom of expression, the Congress passed two important resolutions, much discussed. One resolution condemned the serious violations of freedom of expression for journalists in Palestine and Israel; the other resolution called for protection mechanisms for writers facing harm everywhere.

In keeping with our mission to be vigilant about violations of freedom of expression, the Congress passed two important resolutions, much discussed. One resolution condemned the serious violations of freedom of expression for journalists in Palestine and Israel; the other resolution called for protection mechanisms for writers facing harm everywhere.

2024 PEN International Resolutions

Yet among the grim and intense moments came happy ones. One was the moment when San Miguel PEN’s Judyth Hill was elected chair of the PEN International Women Writers Committee. Another was when the delegates voted to accept a new PEN center, from Dominican Republic, into the fold. Another was the acceptance of a fifth committee in the PEN International structure: the Young Writers Committee.

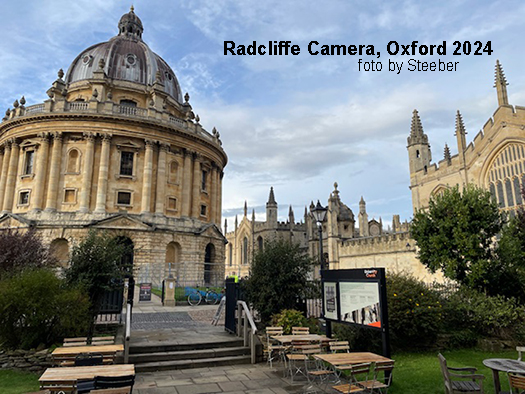

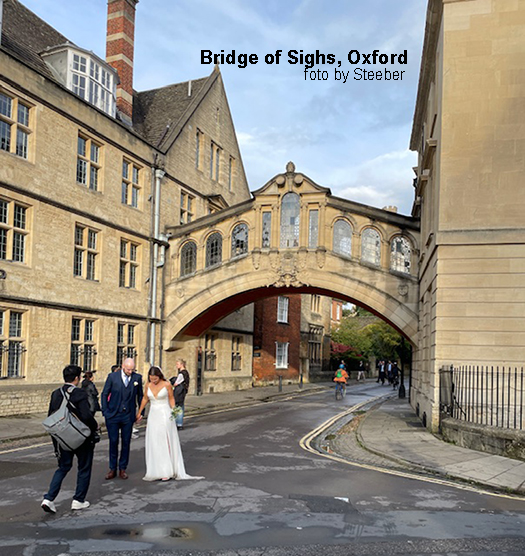

The hours of the conference ran long, thanks to stimulating and relevant evening programs at the Bodleian Library, one of the oldest in Europe, and the Ashmolean Museum. Yet we did have a few hours free one afternoon. Lucina Kathmann and I followed a self-guided walking tour in Oxford center and were able to see Oxford’s oldest house, built in the 1300s; the famous Oxford City Council Covered Market, in existence since the 1770s; the spell-binding Radcliffe Square showcasing the Radcliffe Camera (a library); Oxford University’s official Church of St. Mary the Virgin; All Souls College, from outside its beautiful gate on the square; and the Bridge of Sighs, where a just-married couple was posing for photos. The storm-gods must have been smiling upon us. The rain let up and we were anointed with only a few sprinkles, in stark contrast to our entry into Oxford a few days before.

A poetry reading, during which attendees read aloud their own poetry or prose to great enthusiasm, marked the end of the conference. Paramount as we left this year’s gathering was our ongoing solidarity as a global community in dogged pursuit of safeguards for writers, journalists, and artists around the world.

The author, Sharon Steeber is the President of San Miguel PEN.

https://www.sanmiguelpen.com/